Platform

Use Cases

ACCOUNT SECURITY

Account TakeoverMulti-AccountingAccount SharingIDENTITY & FRAUD

Synthetic IdentitiesIncentive AbuseTransaction FraudPricing

Docs

January 4, 2022

Last updated: January 29, 2025

Terence Eden makes an interesting point on his blog: "CAPTCHAs don’t prove you’re human – they prove you’re American".

Intuitively, this claim makes a lot of sense. CAPTCHAs, like almost everything, are embedded into a cultural context, and if your pool of challenges has been mostly created in one culture, it may not translate very well to another. At its core, this is a matter of the cultural content of CAPTCHAs, rather than their UX per se.

As Eden puts it:

"Guess what, Google? Taxis in my country are generally black. I’ve watched enough movies to know that all of the ones in America are yellow. But in every other country I’ve visited, taxis have been a mish-mash of different hues."

Google's problem here is based on the question data they use vs. who sees it. If all data comes from the same culture (and in Google's case, the same company) you can certainly expect to have challenges that do not translate well to other cultures, in line with Eden's complaint.

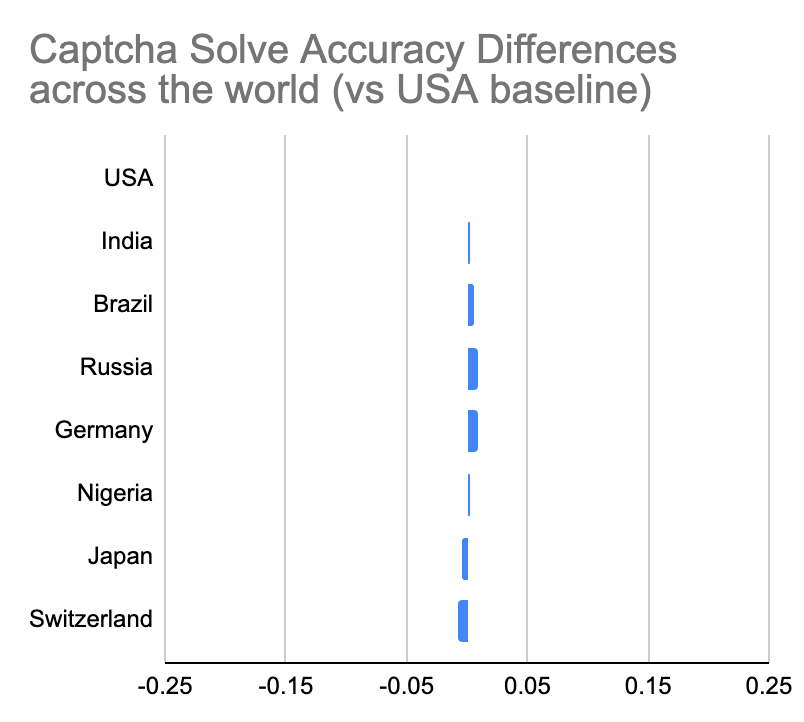

However, our data shows that (for hCaptcha) there is less than 1% variance in solve rates across major countries on every continent. Many countries in fact do slightly better than the US, including Nigeria, India, Brazil and Germany:

hCaptcha Solve Rates across the globe show very little variance

hCaptcha now runs on about 15% of the internet and is used in every country and territory in the world, so we are very much focused on providing a consistent global experience.

Cross-cultural functionality is thus a basic requirement for our service. Making sure that all legitimate users can access content quickly is a critical part of our mission. We provide challenges in 110 languages, and are continuously improving the relevant translations to make sure that our challenges can be solved by everyone.

At hCaptcha, we have taken a different approach from day one.

We test our challenges rigorously, and let challenges self-optimize to determine in which countries or languages they will run, increasing the likelihood of a consistent experience even further. If accuracy is lower than expected, a set of questions will rapidly stop running in the region or language where this effect occurs.

Evidence this is working: uniform solve rates across the globe. If our challenges were easier to solve for some groups, we would expect to see a difference in how people across the globe and across different cultures perform when solving them. In the context of Eden's post, we would expect Americans to do better than people in other countries. Because we have spent years developing systems to avoid this problem, we in fact see just the opposite.

PS: If you find a translation in your language that could use improvements, just email us at support@hcaptcha.com!