Are all residential proxy services criminal organizations?

Some residential proxy vendors are less legitimate than they may seem.

Last updated: July 29th, 2025

Disclaimer: The conclusions within this report are based on analysis performed by hCaptcha. This document reflects our findings as of the date above and is published for informational and security awareness purposes.

Executive Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the residential proxy service industry, revealing a significant disconnect between its purported legitimate uses and actual observed traffic.

Based on analysis of tens of millions of IPs and many millions of requests, the hCaptcha Threat Analysis Group (hTAG) reveals an ecosystem that enables industrial-scale fraud and abuse while operating behind a veneer of legitimacy.

Key Findings

- Majority of Traffic Appears Malicious: Our analysis indicates that between 30% and 95% of traffic on major residential proxy networks is associated with blackhat or greyhat activity, including ad fraud, ticket scalping, and other forms of abuse. Legitimate use cases appear to represent a minority of traffic.

- Core Abuses: The primary drivers of this traffic are ad fraud, search engine manipulation (generating fake clicks to alter rankings), ticket and inventory scalping bots targeting high-demand items, and spam attacks against major online services.

- An Interconnected and Opaque Industry: The market is not composed of hundreds of fully independent providers. Rather, our IP analysis reveals that dozens of separate brands are reselling access to just four distinct underlying IP pools, creating layers of indirection that obscure responsibility.

Traditional Defenses Are Ineffective: The most popular Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) and CDNs struggle to combat these distributed attacks, often detecting less than 10% of malicious requests in some large-scale campaigns, based on our data. IP-based blocking is shown to be completely impractical.

Intro

Residential proxy services sell access to pools of millions of IPs for their customers to avoid rate limits and web firewalls, and they are often effective.

As of August 2025, hCaptcha metrics show leading WAFs/CDNs detecting less than 10% of requests in some attacks using residential proxies. This is unsurprising: each IP may make only one malicious request per day, often interspersed with real traffic.

The IPs in these pools have many sources, including malware botnets and hacked residential routers. Many res-proxy services are advertised explicitly for crime, operate anonymously, and make no secret of their IPs being from botnets.

However, over the past few years some res-proxy vendors previously linked to cybercrime have legitimized themselves, rebranding and in some cases even raising venture capital. These legitimized entities often claim to rent IPs from ISPs directly, or to use opt-in schemes where users agree to share their bandwidth in exchange for very small payments or services like free VPN access.

They can operate in the open because there are a handful of legal use cases for large distributed IP pools, e.g. checking if your ads are actually displayed in different regions. This gives them a veneer of legitimacy, but raises some obvious questions.

For example, what percentage of their total traffic is legitimate? How much of it is likely cybercrime? To what extent are the companies that claim to be sourcing IPs legally really doing so, vs. simply paying criminals for access to botnets?

No one would consider an entity with 95% of its revenue derived from cybercrime to be legitimate, but the opacity of residential proxy services makes calculating this percentage difficult for outsiders.

hCaptcha sees daily attacks on our customers from IPs linked to these res-proxy services, so we decided to attempt to answer these questions comprehensively.

After analyzing many of the largest operators, we now have hard facts. The majority of res-proxy traffic reviewed by the hCaptcha Threat Analysis Group (hTAG) does not appear to be legitimate.

Read on to learn exactly what the traffic mix is on these services, where they may really get their IPs, and how seemingly legitimate companies in this space try to shield themselves from liability for any crime they enable.

Indirection conceals many evils

Res-proxy companies love reseller and affiliate models. Having others resell their services gives them distance from the end-customer if there is a problem.

They use the same model as one of their ways to acquire IPs, presumably to buy plausible deniability or at least make their knowledge and intent regarding any illegal activity harder to prove.

Though some vendors claim to KYC ("know your customer") their users and IP suppliers, these layers of indirection mean the groups that build and maintain these systems often operate unharmed, even as resellers or IP suppliers are occasionally shut down or arrested.

In practice, even direct KYC is not a very effective tool. Identities can be cheaply purchased at scale in many countries. A botnet operator that installs malware on 35,000 devices and cashes out using 2,000 purchased or stolen identities will tend to be able to collect fees for a long time, with only a fraction of their earnings impaired at any given moment as users detect their malware or replace hacked routers.

Similarly, when res-proxy pools use affiliate resellers, they may also delegate KYC checks to them. This means the reseller, who may be a single individual in a country that does not enforce cybercrime laws, may be able to approve new customers and use cases. Even if we assume vendors or resellers have the best of intentions, how many will look twice at a "new startup" with a .ai domain and a fake profile on LinkedIn? Their incentive is to collect customers without asking too many questions.

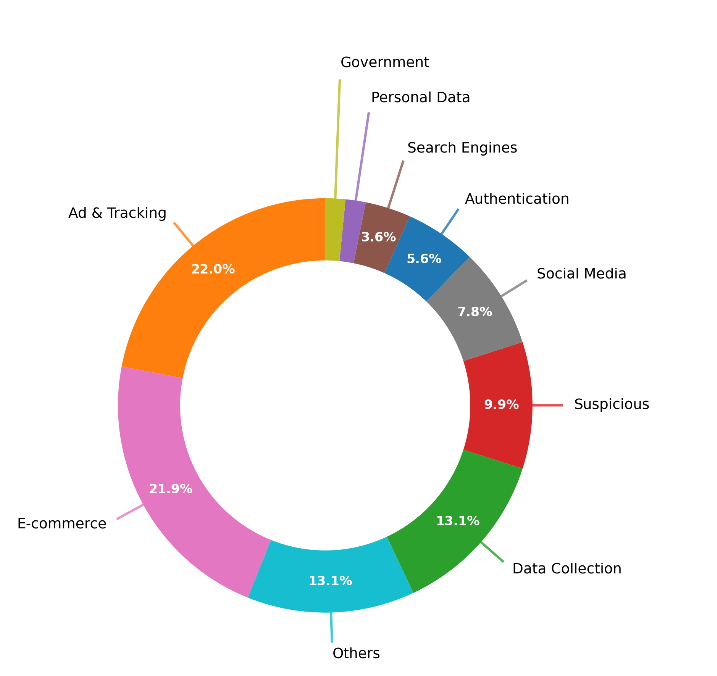

Reselling is rampant, and many IPs are not dedicated to a single provider

After analyzing tens of millions of IPs, hCaptcha has unwound the true relationships between dozens of res-proxy vendors.

The graph below illustrates IP sharing between many well known vendors. More IP overlap puts providers closer to each other.

For example, we identified that well-known Providers A and B both shared a large number of IPs with each other, as well as with the other providers/resellers nearby.

This can happen for many reasons. Users can install multiple res-proxy apps on the same machine at the same time, and they can run in parallel. Botnet operators and other bulk IP providers can equally end up selling the same IP many times.

Finally, many providers appear to be reselling services without clearly disclosing this fact. There seem to be only four distinct IP pools used by dozens of separate brands.

The total number of IPs available to a single customer in a 24 hour period from each provider or reseller also varies greatly, from thousands up to many millions of IPs.

Closer circles show percentage overlap of IPs between vendors

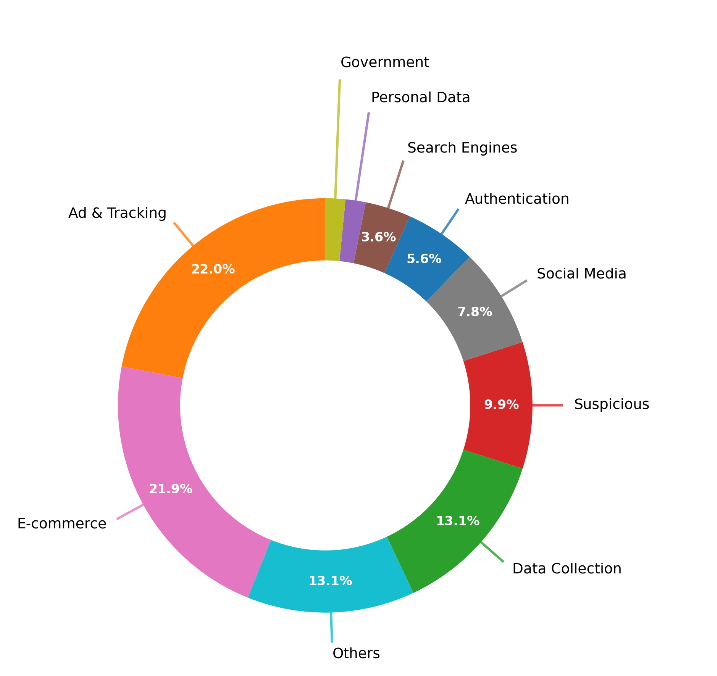

What are these services actually used for?

Search Engine Fraud / SEO Manipulation

A large proportion of requests made on most providers go to Google Search.

Looking into the queries, we can see that most requests are not 'greyhat' SEO, e.g. placement monitoring, but are likely intended to manipulate rankings directly by generating fake clicks. Some fairly sophisticated strategies appear to be deployed, including "personas" using both logged-out and logged-in query patterns to make irrelevant queries, with commercially targeted ones then mixed in.

Aside from generating misleading click signals that presumably boost less relevant sites in the rankings, this kind of activity likely costs Google advertisers who pay for clicks a large amount of wasted ad spend, as plausible automated personas will tend to click on real ads occasionally in order to keep up their pretense.

Ad Fraud

Patterns indicative of likely ad fraud, primarily display network ad fraud, appeared to make up 20-50% of total request volume for many of the res-proxy providers.

This appears to be perpetrated by the site operators. For example, one suspicious gaming website with no terms or privacy policy and no organic inbound links on the web is apparently generating tens of millions of impressions per day using residential IPs across multiple res-proxy providers.

Further research by hCaptcha identified near duplicates of the gaming website on multiple domains with different names, presumably to let the site operators quickly rotate to those new domains and ad accounts if the current site is suspended.

Ticket Scalping / Inventory Sniping Bots

On some providers, a large number of requests to ticketmaster.com and similar sites were being made, especially during major event ticket releases.

Ticket scalping or botting is illegal in many countries and US states, as is any kind of resale above face value of tickets.

Artists intentionally underprice some of their tickets so more fans can come to their shows, and use flat ticket pricing and no-profit resale rules instead of auctions for the same reason. Fans are not the ones primarily using bots: resellers abuse them to profit, effectively stealing from both fans and artists.

A similar dynamic applies to high-demand items like new game console releases, where the item can be immediately resold above list price for a profit. This is also a popular use case for res-proxies, as merchants try to ensure fairness by blocking bots hammering their sites looking for inventory, and bot operators try to avoid those bans.

Authentication attacks and authenticated spam

Traffic patterns indicative of spam and post-login crawling were also observed. Targets included Instagram and X, and other social platforms like Pinterest.

Estimating the abuse proportion

While individual res-proxy providers likely know this number well, informed estimates covering multiple providers have not previously been made public.

The variance in this estimate is due to a combination of factors, including day of week and external traffic patterns. When new and profitable attacks emerge they will tend to quickly consume a large number of requests, causing the abuse percentage to go up. Similarly, while a large number of requests appear likely to be blackhat activity, definitively classifying some activity would require confirming policies with every site being targeted, which is outside the scope of this report.

While Cloudflare's decision to block AI bots from crawling may produce more business for these companies in the short term, it seems likely that legitimate use of residential proxies currently makes up a minority of total traffic for many or all of these services.

Based on analysis over several weeks and many millions of requests, hCaptcha estimates that 30-95% of requests via residential proxy services are either blackhat or greyhat activity on any given day. This number will vary somewhat by provider, but the overall traffic patterns observed were similar across many of the largest services.

We cannot definitively state that this estimate is accurate across the entirety of any given provider's traffic without access to their internal data, but the consistency of the patterns observed across providers, countries, and days sampled is highly suggestive.

What should be done about residential proxy services?

It is impossible to entirely stop cybercrime, and it is unlikely to entirely shut down these kinds of services, though it would be a net positive for everyone on the internet.

However, this does not mean we should encourage and legitimize companies that clearly profit from the illegal activities of their customers.

All online services that offer self signup without exhaustive background checks and financial penalties for misbehavior will see some level of use or abuse by criminals, but this is very different from targeting those same criminals as customers and suppliers and optimizing your business model for deniability.

We believe that most companies in this space would see their revenues shrink dramatically if suitable regulation or enforcement were put in place, and the savvy ones will likely lobby heavily to avoid criminalization or strict regulation in larger markets. Regardless, regulatory solutions may be the most effective remedy.

How was this analysis performed?

hTAG verified and analyzed logs of proxy data flows and related datasets shared by independent security researchers, combining these results with analysis of recent attacks on hCaptcha Enterprise customers using confirmed residential proxy IP pools, and correlating them with detection and block rates from WAFs and security CDNs related to those attacks.

Analysis data was collected by independent researchers over several weeks in multiple countries in order to limit any sample bias in IP location or collection times.

How can operators of online services defend themselves?

hCaptcha data indicates that the top WAFs and security CDNs are ineffective against large-scale residential IP proxy attacks.

Similarly, buying lists of residential IP proxies is extremely error-prone, and these lists should not be used for blocking traffic. They become stale almost immediately, and are extremely inaccurate in our analysis.

The same IP may be used by 100 customers in a "carrier grade NAT" scenario, as is common in Latin America and Asia. The fact that a single device on the IP is part of a botnet does not mean that all of the traffic is bad: there are 99 other customers generating real, non-botnet traffic at the same time, and the IPs used by ISPs rotate regularly, so the botnet user may not even be using the same IP a few hours after the initial signal is recorded by the IP list provider.

Blocking at the IP level is thus completely impractical in many applications. A retailer does not want to reject 99 real customers in order to have 50% odds of blocking one bad user.

The most robust solution is holistic intent-based risk analysis at the individual session level, as provided by services like hCaptcha Enterprise.

hCaptcha is uniquely focused on user privacy, and can operate without any access to PII like an IP address, name, address, email, or other uniquely identifying information. This makes it especially suited to detecting large-scale distributed attacks, no matter how many devices and IP addresses they use.